by Megan Kinkade

by Megan Kinkade

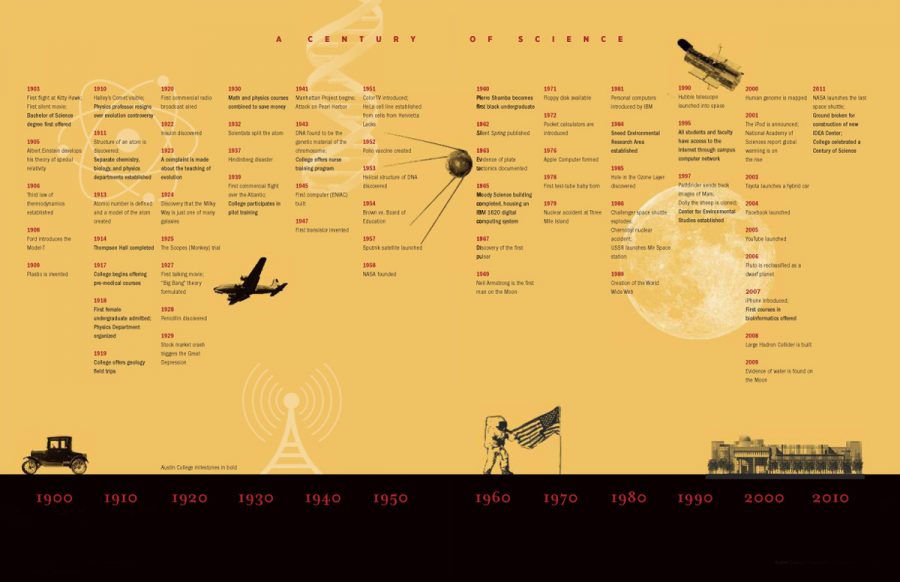

A preeminent liberal arts education has been the foundation of Austin College since its founding in 1849. But until 1911, science courses were integrated into the curriculum without separate divisions. Since 1911, the College has continually worked to say ahead of constant research developments, moving from studying only external cellular structure with sunlight powered microscopes to analyzing cellular DNA with today’s computer-linked fluorescent microscopes.

As Austin College prepared to celebrate a century of science education, faculty scanned the history books and College Archives to gain a perspective on what the last 100 years of science education at Austin College has entailed. They discovered a faculty who had been dedicated to teaching and stories of young men and women committed to learning and taking their education into their own communities as researchers, professors, business leaders, and physicians—much as today’s young men and women will do.

1849 to 1910

In 1853, the College established an uncommon relationship with the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. In exchange for data on Texas weather and native Texan plant and animal specimens, the Smithsonian provided the College materials, books, science pamphlets, maps, and mineral specimens, giving the College a head start on a science curriculum.

Additionally, College founder Dr. Daniel Baker was given “not less than $500 for chemicals and apparatus” on his fourth trip to Washington, D.C., and New York. By the late 1880s, the sciences were staffed with well-trained professors such as George Snedecor in mathematics. Snedecor discovered a process he called the “F Distribution,” which became a key element in the analysis of statistical variance.

The first Bachelor of Science degrees were offered in 1903 to those students who took a heavier concentration of courses in the sciences. Courses of the time included surveying and navigation, differential and integral calculus, hydrodynamics, electricity, and magnetism.

1910-1920

1910-1920

There was a minor crisis among the faculty in the 1910s, when a student studying for ministerial work complained to the College president that evolution was included as a scientific fact in one of the textbooks. All the science faculty members were called in for questioning, and it was discovered that the book was owned by Dr. Harry Sharp, a physics professor. He voluntarily resigned when questions about his lack of religious faith displeased the heavily ministerial Board of Trustees.

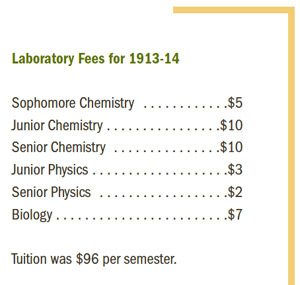

That decade was one of great change within the College. The sciences expanded to include engineering curriculum, and the increase in courses led to the founding of a separate department for chemistry and the combined department of biology and physics. The lone classroom building was remodeled to meet the growing need for space, but before the project was complete, a homesick 15-year-old student arsonist burned Old Main in 1913. All the materials, books, and science equipment was lost in the fire.

Undaunted, President Clyce began fundraising efforts immediately, and Thompson Hall was constructed by the end of the year, replete with “modern science laboratories.” In addition to having gas power as a backup, the new building was equipped with the latest modern advancement: electrical power.

Austin College already was developing a reputation as a leader in pre-medical studies. One of the first alumni to earn his medical degree was Mandred W. Comfort, who graduated in 1916 and became a surgeon with the famous Mayo Clinic. The College began offering specific pre-medical courses in 1919, and already had started a separate department for geology and physics. The geology courses were popular; on Saturdays, students had the opportunity to scour riverbeds in Texas and Oklahoma, looking for fossils.

1920-1930

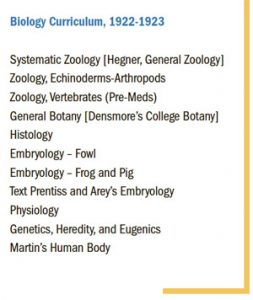

By 1920, courses in vertebrate and invertebrate zoology became requirements for all biology students. But the biology curriculum still was not without controversy: In 1923, a Ku Klux Klansman confronted one of the biology professors on his teaching of evolution. In response, the Board of Trustees called for each faculty member to agree to a loyalty oath. Each assured the board members of his Christian faith, and promised not to teach anything “opposed to any doctrine of the standards of the Presbyterian Church,” and faculty were allowed to continue their lessons.

Bradshaw Frederick Armendt, who graduated in 1921 with an emphasis in physics, was known for “two ruling passions—chemistry and girls, and he spends his time breaking beakers and hearts alternately,” according to the 1921 Chromascope. Armendt was called back to the College as a professor a few years after graduation, and he greatly influenced students of that era.

Armendt worked with his former chemistry professor, Charles Carrington Scott, to refine the science curriculum, update the equipment, and expand the number of available courses. Under C.C. Scott’s tutelage, the first four students to earn a Ph.D. in the sciences graduated and went on to institutions such as Yale University.

Armendt shepherded pre-medical students in particular, founding the College’s first pre-medical society in 1927.

1930-1940

The stock market crash of 1929 didn’t immediately impact the College, but by the mid-’30s, the math and physics departments were combined to save money. Students and faculty struggled to make ends meet during the Great Depression, the faculty shrinking to eight people at the height of the financial problems.

The stock market crash of 1929 didn’t immediately impact the College, but by the mid-’30s, the math and physics departments were combined to save money. Students and faculty struggled to make ends meet during the Great Depression, the faculty shrinking to eight people at the height of the financial problems.

In 1932, after a failed business venture, alumnus George Landolt was hired as professor of chemistry and business manager for the College. He used his great ingenuity to keep the College afloat, willing to make unusual trades: Landolt once accepted three cows as a tuition payment. He then “paid” those cows to biology professor and dean of students James Moorman as his salary for the month. Moorman gave the animals to his landlord to pay his rent.

In 1935, Moorman became the dean of students following a College tragedy. Students broke into the chemistry laboratory late at night and drank the wood alcohol they found. They became violently ill and two freshmen died. When police tried to learn more about the events, they discovered that students would speak openly only to Moorman because of their great trust in him. He was promoted, and was affectionately known as “Dean” to the students.

He once said, “I love my faculty and students. It is easy for me to get them to do whatever I want. The difficult part is having the wisdom to influence them in the right direction.”

As the country slowly moved out of financial crisis by 1939, the College joined the Civilian Pilot Training Program to open the doors to more students. Science professors took on additional courses to organize the ground school courses in mathematics and meteorology, while eager pilots learned to fly at the municipal airport. The timing was fortuitous.

1940-1950

In 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and every American was called to help in the war effort. The civilian pilots trained at Austin College joined the armed forces, and the College adopted a more military form of education. As the war stretched on and the young men were enlisted to the service, the College further developed programs for women. In 1943, the College joined with Wilson N. Jones Hospital to offer combined classroom and on-the-job training for nurses.

Meanwhile, 1919 alumnus Percival Keith had a great influence on the world as a researcher on the Manhattan Project, which led to the creation of the atomic bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan. (Read more about Percival Keith)

1950-1960

1950-1960

With the growth of interest in the sciences due to the “Space Race,” the College sought funds to improve the buildings and curriculum. The College received a $10,000 grant from the Ford Foundation for a comprehensive survey of the school’s operations in 1952, followed the next few years with several additional gifts.

One of the improvements was a renovation of Thompson Hall in 1957; the gaspower system was removed, the electric system and plumbing replaced, and central heat and air conditioning installed. The changes to the building were matched with changes in the curriculum. The Basic Integrated Studies program combined mathematics and the natural sciences. Professor A.J. Carlson noted: “Mathematics and physics courses in the first year were to lay a foundation in the second year for chemistry, geology, and biology, taught partly by television.”

The 1950s also saw the College’s first nonwhite professor. Professor O. Kumar Mitter, a foreign exchange faculty member from India, taught mathematics for several years.

1960-1970

In large part due to the changes wrought by the Ford Foundation grant, the College was highlighted as a “school to watch” in a 1960 TIME magazine feature.

By 1961, the Basic Integrated Studies curriculum gave way to Basic Studies, and math and the sciences again were separate divisions. The curriculum also did away with the separate Bachelor of Science degree, as there were no longer many distinctions between it and the Bachelor of Arts degree.

Biology professors Howard McCarley ’48 and “Bud” Bryant enriched the premedical program. Austin College: A Sesquicentennial History, written by Light T. Cummins of the current history faculty, notes: “Austin College earned a reputation by the late 1960s as having one of the region’s truly outstanding pre-medical programs.”

The biggest development came in 1965 with the construction of the Moody Science building upon receipt of a $1 million grant from the Moody Foundation. The building included such timely features as an astronomical observation platform, a greenhouse, and a room for radioactive materials. The building also was a designated safe zone in the event of a nuclear attack.

The Biology Department was the best-prepared for the move into the new building. Faculty organized the football team to help; players ran up the stairs of the Administration building, picked up a box, ran down the stairs and across the lawn, up to the third floor of Moody Science Center to leave the box, only to return and pick up another.

With the construction of Moody Science came the founding of the computer Science Department. The Hoblitzelle Computer Center, located in the first floor and basement of the building, housed an IBM 1620 “digital computing system” with up to eight terminals for student workers. The computer was the size of a large desk and was used mainly for administrative data entry.

The Basic Decisions Program in 1967 introduced January Term. Early on-campus offerings consisted mostly of lectures: a chemistry course dealing with laboratory procedures included 20 hours of lecture and 100 hours of laboratory time.

1970-1980

The changes in the curriculum extended into the next decade. In their first semester, students now took two courses for seven weeks, meaning the science curriculum had to be completely rethought.

Michael Imhoff, currently vice president for Academic Affairs and dean of the faculty, joined the chemistry department faculty in 1970. “The faculty members took the curriculum and dumped it on a table and re-concepted everything,” he said. They created a new kind of teaching: “paradigm chemistry,” which changed the emphasis from memorization to basic concepts. “It was a challenge because it was very work intensive and all these students came in without any prior experience,” Imhoff said.

Students in the era had some strange proclivities: it was customary for students in anatomy classes to celebrate the end of the semester by “decorating” the campus with their dissected laboratory carcasses. Once, a new librarian had not been warned of the practice, and panicked, believing there to be a rogue cat-killer on campus, before the prank was explained.

The ’70s also saw the growth of the Health Sciences Club, which attracted a large student membership for those interested in medical and dental careers. The club brought speakers to campus and aided in medical school applications. The Society of Physics Students promoted “an interest in the field of physics through meetings, presenting guest lectures, field trips, films, and projects.”

The first American black professor also joined the Austin College sciences, with the inclusion of Abraham Nelson, Jr., in mathematics in 1972.

1980-1990

“Students in the ’80s were a little more uptight, more career-focused, than the students in the ’70s,” Imhoff said. To adapt to the changing needs of students, the curriculum shifted to the modern schedule. In 1984, the Heritage of Western Culture sequence was revised to require a science-oriented course, which introduced students to four or five fundamental scientific topics, such as evolution, modern physics, genetics, and the environment. For the first time, students participated in molecular biology courses.

1990-2000

By the ’90s, the Heritage course no longer was ideal. “It was a great course on principle, but we just didn’t have the resources to do the reinforcement,” Imhoff said. “Two hundred students introduced to the theory of relativity for the first time who are just hanging on … you lose them when it gets more complicated.” The Heritage course ended, and students took separate science requirements instead.

In 1995, faculty and campus offices were connected to the internet, and email became a primary mode of communication. The student resident halls were modified over the next few years to provide internet access in each room.

2000-2011

Austin College has maintained its reputation for excellence in the sciences, with an 80 percent acceptance rate to health sciences programs. Student research in the sciences, often in conjunction with faculty, has become a thriving program and outgrown available laboratory space. The Center for Environmental Studies has added a new area of study and new opportunities in the sciences. Faculty positions were added to bring the sciences faculty total to 26.

The Future

The Future

Austin College administrators broke ground on a new science building, the IDEA Center, on June 3, 2011. The IDEA Center emphasizes inquiry, discovery, entrepreneurship, and access. Plans include 16 classrooms, 32 advanced laboratory-classrooms, 40 faculty offices, a 108-seat auditorium, and an observatory with a state-of-the-art telescope. The center will provide the educational home of the departments of biology, chemistry, computer science, environmental studies, mathematics, and physics. The building will be LEED Silver certified for environmentally friendly construction.

The new building, scheduled to open in fall 2013, will allow continued modern science teaching and learning and position the College for another 100 years of excellence in the sciences.

Eye on the Future

Comments? Email editor@austincollege.edu.