by Megan Kinkade and Vickie Kirby

Austin College alumni certainly can be found in prestigious career roles around the world. Many of those, however, do not base success on the level of promotion they have attained, but on the degree of satisfaction they enjoy. And that satisfaction sometimes has little connection to financial compensation. Ask members of the Austin College Class of 2011 their criteria for future success and, in one form or another, a large percentage of their answers will come down to “doing enjoyable work and being able to benefit others.” That perspective is in agreement with a basic value of the Austin College experience. “One of the most fundamental elements of a liberal arts education is the idea of ‘public good’ and we try to create an environment in which that is emphasized,” said Austin College President Marjorie Hass. “The education we provide is about preparing alumni for success, which means being part of making the world a better place, not just amassing financial gains.”

Over the next several issues, Austin College Magazine will offer a look at “successful” alumni. They may be at the top of their field; they may be just setting out. Perhaps they’re recovering from setbacks or exploring new passions in retirement. For some, success might mean showing up every day and doing their best work with a smile, without recognition or acclaim, but making the world a better place.

Working for the Cause

Helen Lowman ’88 really does want world peace.

She’s been sharing cultures and experiences that promote global peace nearly all her adult life, much of the time as a member of the Peace Corps staff.

This year, the Peace Corps is commemorating 50 years of service that had its beginnings with John F. Kennedy challenging college students to work for the cause of peace by living and working in developing countries around the globe.

Many years later, Helen accepted that challenge by becoming a Peace Corps volunteer after graduating from Austin College in 1988. Since that experience, she has held a number of Peace Corps and non-Peace Corps jobs. (Peace Corps employees can work only five years, then must be away at least five years before returning to the organization—designed to keep individuals and ideas fresh.)

In July 2010, Helen took on what she calls “the best job in Washington” when she was appointed by President Barack Obama as the Peace Corps regional director for Europe, the Mediterranean, and Asia.

Beginnings

Beginnings

As a high school student, Helen spent a summer in Chile as an exchange student and became aware of a world far beyond the small town and cattle ranch she had known.

At Austin College, her mentor Shelly Williams, now professor emeritus of political science, guided her to consider international studies. “That was clearly the right way to go,” Helen said. “I have stayed in my study area my entire career.”

Helen spent her junior year of college in a study abroad program in Madrid, Spain. While there, she decided that she wanted to join the Peace Corps. Accepted, she spent nearly three years in a rural village in Thailand where she taught English to middle school students. She lived on the school campus in a house with two Thai teachers, took cold bucket showers and did laundry at the well, taught school, interacted with students, and planned her next lessons. She visited with other teachers and wrote letters to friends and family. “Life was very simple,” Helen said.

“My experiences opened my eyes to the way the majority of the world lives,” Helen said. “I realized how fortunate we are in the United States—as well as our responsibilities to the rest of the world.”

Next Steps

Next Steps

Back in the U.S., Helen completed a master’s degree at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies. She then worked for Biotechna Environmental in London for one year, then took a position with the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission.

A chance to go back to the Peace Corps arose and she became associate director of environmental education for China. After 18 months, she became the country director for China, serving as liaison to the embassy ambassador and having oversight responsibility for all program operations in that country: administration, programming and training, safety and security, and medical. As country director she also traveled much of the time, visiting volunteers and local partners. While she was country director, the SARS crisis necessitated suspension of service in China, and Helen became country director for Mongolia for one year while negotiating to reopen the programs in China, then returning there to work through her fifth year.

The next five years, Helen was vice president for intercultural education and quality at AFS Intercultural Programs/USA in New York, which maintains the world’s largest high school exchange program.

Today

Last July, Helen got the call for the job she had wanted for years: Peace Corps regional director for Europe, Mediterranean, and Asia. Peace Corps programs operate in 20 countries in the region, and by the end of June, Helen hoped to visit all of them. “The country directors are in charge of operations,” she said. “My job is advocating for my countries with the State Department, representing the interests of the posts, and letting the senior team at the Peace Corps know what is going on.”

Last July, Helen got the call for the job she had wanted for years: Peace Corps regional director for Europe, Mediterranean, and Asia. Peace Corps programs operate in 20 countries in the region, and by the end of June, Helen hoped to visit all of them. “The country directors are in charge of operations,” she said. “My job is advocating for my countries with the State Department, representing the interests of the posts, and letting the senior team at the Peace Corps know what is going on.”

She also speaks by phone with country directors almost every day—quite a logistical challenge. The region between Morocco and the Philippines includes 17 times zones—not to mention the additional zones between there and Helen’s Washington, D.C., office. When she makes a morning call to the Philippines, that country director already has gone home and put the children to bed.

Logistics and long hours of travel don’t dampen Helen’s enthusiasm for her work. “This is the best job I’ve ever had,” Helen said. “I loved being country director, but I love what I do now. Peace Corps is a great organization and everyone who works here believes passionately in what we do. When I wake up in the morning, I want to go to work and I’m not looking at the clock waiting for the end of the day.”

Logistics and long hours of travel don’t dampen Helen’s enthusiasm for her work. “This is the best job I’ve ever had,” Helen said. “I loved being country director, but I love what I do now. Peace Corps is a great organization and everyone who works here believes passionately in what we do. When I wake up in the morning, I want to go to work and I’m not looking at the clock waiting for the end of the day.”

When the day does end, Helen is becoming acquainted with the “amazing city” she now calls home, enjoying Kennedy Center presentations and museums and other sites. But even at day’s end, her work is with her as she is never far from her phone, and every ring brings momentary apprehension of a difficulty in her region.

The Future

Of course, Helen is always planning. “There are several countries in my region that have expressed interest in having a Peace Corps presence, which I would love to see,” she said. “There are some countries where I think we really can make a difference.”

Given enough five-year work periods, Helen may carry the Peace Corps message of friendship totally around the globe one day.

That’s a passion for peace.

No Bones About It

No Bones About It

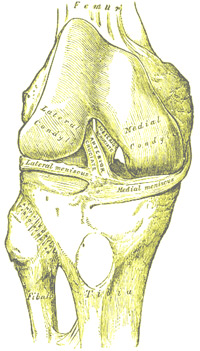

George Zoys ’91 is one of the best in his craft—no bones about it. Actually, he’s all about bones.

George is one of Dallas’ top orthopedic surgeons; he’s been included in D Magazine’s Best Doctors list five times.

As an orthopedic surgeon, he focuses on repairing bones and joints. He performs hip replacements, sports medicine, joint surgery, and arthroscopic knee surgeries.

“With orthopedics, you see something broken, you fix it. You see the results right away,” he said. “And it’s fun working with saws and hammers,” he added with a laugh.

George came to Austin College because of its reputation as good preparation for medical school. His older brother had attended, and the College “had an excellent reputation, especially for medicine.” “The curriculum, if you were trying to get into medicine, was one that required a lot of studying and discipline. In order to get through it, you had to have certain habits, like hard work and staying up late studying. When you went to medical school residency, there wasn’t that much of a change,” he said. “I think that having strenuous course loads and a hard curriculum gets you attuned for what it’s like in graduate school and medical school.”

He majored in chemistry and participated in the Chemistry Society, the Physics Society, and intramural sports, before going on to medical school at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, Texas. He completed a residency in orthopedic surgery there, at one of the top orthopedic surgery hospitals in the country.

Then he was selected for a fellowship in Australia—where he provided orthopedic support for the 2000 Sydney Olympics. “If someone was injured and needed surgery, we did it. Gymnasts had knee injuries. One of the equestrians broke his ankle, but most of the time it was just hanging out and watching them,” he said. “It was fun. It wasn’t hard work, but it was fun seeing all these finely-tuned athletes from all over the world. We all volunteered to cover—we didn’t get paid for it, of course—and I was there learning all the subspecialties, and it was awesome.”

Then he was selected for a fellowship in Australia—where he provided orthopedic support for the 2000 Sydney Olympics. “If someone was injured and needed surgery, we did it. Gymnasts had knee injuries. One of the equestrians broke his ankle, but most of the time it was just hanging out and watching them,” he said. “It was fun. It wasn’t hard work, but it was fun seeing all these finely-tuned athletes from all over the world. We all volunteered to cover—we didn’t get paid for it, of course—and I was there learning all the subspecialties, and it was awesome.”

After his time with the Olympians, George participated in three fellowships in Australia, learning subspecialties in sports medicine, shoulder orthopedics, and foot and ankle surgery. In short, he is highly specialized in many subjects.

Then he came back to North Texas and joined a practice in Garland. He has grown that single practice to two facilities, has staff privileges at Lake Point Hospital, is an active staff member of Baylor Hospital of Garland, is chairman of the Medical Executive Committee for North Garland Surgery—which he began—and is president of the Walnut Medical Association. On top of that, he volunteers with high school football teams, keeping young athletes in shape, and teaches cadaver demonstrations for high school students interested in medicine.

“I think that there are a lot of people that can do good work, and operate well for one type of surgery, but what sets me apart is my desire to be among those who really go the extra mile to care for their patient, be nice to their patient, and be available in the middle of the night. If I’m on-call, I’ll be there. I try to be as available as possible, for patients and other docs who need me. I try to volunteer in the community and go the extra mile, call my patients at home,” he said.

In his practice, George can treat “anyone from 2 to 102.” He works with professional athletes and “weekend warriors,” young athletes and grandparents. But he aims to treat everyone well.

“I remember this old sponsor I used to work with during my residency,” George said. “He used to say, ‘Treat everyone like they own a Cadillac. Your patients put their trust in you, and you just want to do the best you can.’”

More Successes

The Poetry of Living

The Poetry of Living

RonAmber Deloney’s career as a poet began in first grade, when she performed her first dramatic reading of a poem, Shel Silverstein’s “Boa Constrictor,” for a school presentation.

RonAmber continued writing and performing poetry throughout high school and college, frequently performing in the dining hall or at Black Expressions club presentations. She studied English and German, living for a year in the German wing of the Jordan Family Language House. It wasn’t until RonAmber studied German in Vienna, Austria, that she delved deeper into poetry as more than a sometime-hobby.

“Poetry is always a part of my life story, so for me, poetry is important because it still remains that one thing that hasn’t been bruised by hype and media. It had its moment on Broadway, and there are attempts to commercialize it, but it’s still that thing that is kind of underground,” she said.

“There’s a certain sort of intimacy that remains with poetry that I find very important to the arts.”

She became particularly interested in slam poetry, two poets reading their original poetry in a back-and-forth competition. When she returned from studying in Vienna, she talked with her mentor, Jim Knowlton of the German faculty, about the slam poetry interest. He recommended she apply for a Fulbright grant, and before she knew it, she was in Berlin, Germany, to study the slam poetry scene. Her 10-month Fulbright became a 16-month term of study, and she ended up staying in Berlin.

“I really just was in the city, meeting people, going to different events, observing the scene there, and then I recognized there weren’t a lot of people of color performing. I got involved with some organizations and we started to host our own open nights. Then I started hosting my own slam poetry nights. I did that for the three and a half years I was there,” RonAmber said.

“I really just was in the city, meeting people, going to different events, observing the scene there, and then I recognized there weren’t a lot of people of color performing. I got involved with some organizations and we started to host our own open nights. Then I started hosting my own slam poetry nights. I did that for the three and a half years I was there,” RonAmber said.

RonAmber also recorded a spoken word album, Of Brickwalls and Breezeways, with The New Night Babies, a group she helped form while in Berlin. Their music includes original poetry and lyrics, hip-hop rhythms, and often is performed in German and French as well as English. (Listen to tracks from New Night Babies new album, “Lilac and Rapeseed”).

Her poetry often is a social commentary. “I talk about the relationships between people, how we get along and understand each other—or don’t. I describe a lot of common, normal people, and the issues happening with them. I try to talk about what I see around me,” she said.

RonAmber kept busy while in Berlin. “I was involved with the House of World Cultures,” an experimental art venue, she said. “I was doing an internship with the Berlin Poetry Festival. I was an agent for the Last Poets”—a group of poets and musicians that grew out of the American civil rights movement of the 1960s—“and they had five shows in Europe. It was amazing.”

Back in the United States, she continued her education in New York City. She started with a master’s degree in art politics from New York University, and in May completed a master’s degree in administrative education from St. John’s University.

RonAmber intends to move back to the southern United States and teach “through the lens of poetry.” Though she loved her student teaching experience this spring (high school English), she doesn’t want to be a classroom teacher. “I enjoy teaching social justice topics,” she said. “While completing my degree at NYU, I spent eight weeks volunteering as an intergroup dialogue facilitator with the Center for Multicultural Education and Programs at NYU, talking with undergraduate students about race and ethnicity. This experience showed me how important it is for students to have the words necessary to name, evaluate, and dissect the social constructs that define them. I really feel that the more students are empowered as intellectuals, the better chance we stand at moving toward world peace and achieving a more just, understanding world for all people.”

Of course, she’s not giving up her love of learning—“I’d like to do stints abroad and learn French”—and her passion for poetry sustains her. “When I perform I feel like I’m standing up for myself as a human being, giving thanks for being born, and showing that I really do appreciate life.”

![]()

See additional information about RonAmber and read some of her poetry.

The Man of Steel

One day in 1984, Bill Courtney ’83 offered to answer the phones at his student-worker job at Southern Methodist University’s career center so that his coworkers could have a break. He took one call that would set the path for his life.

“I got a call from a guy with a typical east Texas accent, and he wanted to place a job. I told him ‘I can’t help you, but they can help when they get back.’ But he was very insistent,” Bill said. The caller asked what Bill did; Bill explained he was studying for his master’s degree in business administration. The caller told him he would double Bill’s wage and asked him to come down for an interview by 5 p.m.

“He said, ‘you might be missing the opportunity of a lifetime,’ so I said, ‘I guess it can’t hurt,’” Bill explained. Bill went to interview at a small manufacturing company in Dallas, and accepted the job. He later found out he had helped the caller, the owner of a construction materials company, win a $5 bet—that he could hire an MBA student by 5 p.m. that day.

Within six months, Bill received a big promotion: heading up a new production facility in Ohio. He moved, and shepherded the 25-person construction supply company into the country’s No. 1 producer of steel framing materials, with 13 facilities and more than 1,400 employees. The CEO of ClarkDietrich Building Systems since 1985, Bill sometimes is known as “the king of studs.”

His products are in buildings around the world, including residential housing, hospitals, Yankee Stadium, and the Dallas Cowboys Stadium. ClarkDietrich steel frames will be used in the new World Trade Center in New York, a project in which Courtney is excited to be included. “We’ll be the piece right under ‘Never Forget,’” he said.

Bill, the son of missionaries, grew up in Guatemala, and had thought he would pursue a career in international business. “But that isn’t what happened,” he said. The liberal arts background gained at Austin College allowed him to be flexible when opportunity called. “Austin College taught me to be very open-minded and look at any event as an opportunity,” he said. “Austin College opened my mind, and, it’s very true, it taught me how to think and be a well-balanced person.”

“I was a scholarship and financial aid kid at Austin College,” Bill said, paying for his education through work study, loans, and scholarship awards. Today, Bill and his wife, Patty Manning-Courtney ’87, contribute to Austin College in what Bill termed “a kind of pay-it-forward way,” creating the Manning-Courtney Family Sponsored Founders Scholarship. They also have made gifts toward the new IDEA Center and are part of the Kangaroo Housing consortium that is making the new junior and senior housing available for the fall.

Bill greatly credits Austin College with his success, so much so that he modeled his company’s core values after those he learned at the College: do the right thing, look for creative solutions, embrace positive energy and teamwork, and—very important to a liberal arts education—have a balanced life.

“Balanced life” is a core value of Bill’s company. The company leadership doesn’t want employees to live to work, but to work to live. That doesn’t mean we don’t want them to work hard and be committed to their jobs, Bill said, but living each segment of life fully brings positive energy and outcomes to every other segment. “We use that value to recruit and maintain well-rounded employees, who are positive, energetic, and creative people.”

Success, Bill said, comes down to two important elements: passion and progress. “I’m just as excited today, 26 years later, about walking into work as the first day I arrived.” But Bill believes just being passionate is not enough; it’s important to leave the world a better place. “That’s where progress comes in—for me what’s important is to improve the industry and this company and to make things better for the people who work here.”

Being a good father and husband is foundational for Bill; life in the family’s Cincinnati home also keeps him very busy. He and his wife, a physician, have three children—a daughter in elementary school and sons in middle school and high school. Between his job, involvement in his industry association, his children’s schools and school foundation, and their church, Bill has a fulfilling life and career. “When you find yourself at the end of your life, you want to be surrounded by friends and family,” he said. “I tell my kids to invest themselves in that.”

Being a good father and husband is foundational for Bill; life in the family’s Cincinnati home also keeps him very busy. He and his wife, a physician, have three children—a daughter in elementary school and sons in middle school and high school. Between his job, involvement in his industry association, his children’s schools and school foundation, and their church, Bill has a fulfilling life and career. “When you find yourself at the end of your life, you want to be surrounded by friends and family,” he said. “I tell my kids to invest themselves in that.”

He and his wife have been “recruiting” their sons to think about Austin College. Their years at the College provided a pretty good start for Bill and Patty on their lives of success. Passing on the tradition may be one more way to pay it forward.

Alumni with unique careers, out-of-the-ordinary twists in their career path, or other interesting stories to tell, please write editor@austincollege.edu with the highlights.