by Leigh-Ellen Romm

Google it: the writer’s life.

Up pops page after page of expectations, recommendations, admonitions, and advice. Even though there is copy everywhere from the back of the cereal box to the front of The New York Times, the writer’s life does seem a little mysterious. After all, how do they get to do that? And still eat?

The Austin College graduates profiled here have succeeded in different writing fields by following a common rule: work hard. It’s less about muse and more about discipline when developing and growing as a writer.

Mystery author Deborah Crombie, blogger and cookbook author Lisa Fain, ABC news senior writer Kim Powers, fantasy novelist and artist Robert Stikmanz, and academic scholar Jennifer Wenzel share their journeys from Austin College to writer’s life. As varied as their fields of expertise, they agree the liberal arts education provided them the tools to seize opportunities.

DEBORAH CROMBIE

DEBORAH CROMBIE

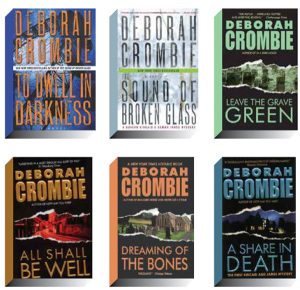

A Plot Twist Leads to Best Seller List

Deborah Crombie graduated in 1977 from Austin College with a degree in biology. But life takes turns, like a mystery unfolding. Her graduate work and travel revealed a passion for England—and for writing. Her liberal arts degree helped equip her with the discipline to pursue it. With her fictional characters Detective Superintendent Duncan Kincaid and Sergeant Gemma James, Deborah has filled the shelves with suspense novels over the last 20 years. A New York Times-Best Selling author, she released her 16th novel, To Dwell in Darkness in September and is at work on the next. Deborah lives in McKinney, Texas, and travels often to England for research. To learn more about Deborah, visit her website.

If you could cast an actor and actress in the roles of Duncan Kincaid and Gemma James, who would you cast?

If you could cast an actor and actress in the roles of Duncan Kincaid and Gemma James, who would you cast?

DC: I’ve been indulging in some fantasy casting as there is an option in place for the development of a UK TV series, but no one ever seems quite right. I think I’d really like to see actors who are not already terribly well-known take the roles and make them their own.

As a young reader, were you always drawn to mysteries? Do you especially like any other genre?

DC: Oh, yes, I started with the Bobbsey Twins and Nancy Drew! Then I discovered Agatha Christie and other Golden Age writers, and from there I moved on to more contemporary work. But I also was an avid reader of fantasy and science fiction, and those genres are still a treat for me to read. I love historical fiction as well.

How important is fellowship and interaction with other writers? What are some ways you develop this?

DC: One of the most rewarding things about my more-than-20 years as a published writer has been the friendship and support of other writers. I don’t know if this is true of other genres, but the crime fiction community is a close one, and over the years, other writers have provided invaluable support and encouragement. I hope I’m able to give some of the same to newer writers.

I highly recommend going to writers conferences and workshops, or to fan conferences if you are interested in a genre that accommodates that. You’ll meet not only published writers but other aspiring writers who may become your lifelong

friends. Oh, and if you go to conferences or conventions, hang out in the bar whether you drink or not. It’s where all the socializing goes on!

Who do you have in mind when you’re writing a story? Can you describe your readers?

DC: It’s not something I really think about. I have male and female readers, so I don’t write to a particular gender audience, although women do make up a much larger percentage of the general reading audience. Older people read more, too, but I don’t age target—I’d like readers from high school on to enjoy my books.

Our readers may include students who might be exploring a writing career. As a successful writer, what advice would you give them to prepare for that field?

Our readers may include students who might be exploring a writing career. As a successful writer, what advice would you give them to prepare for that field?

DC: Read, read, read! There is no substitute! I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had people tell me they want to write a best seller, but when you ask them what they read, they can’t tell you. You can’t write well if you don’t read.

And then write what you love. Don’t worry about whether it fits the market—the market changes all the time, and you can never keep up with it. There is always room for another book if it’s written with enough passion and skill. Or who knows, you might start a new trend!

Practice, practice, practice. Hone your skills. Examine the work of writers you love and figure out why you like it. There is nothing wrong with copying another writer’s style when you are starting out. If you keep writing, you will develop your own voice.

Take advantage of resources. There’s no excuse for not knowing the basics of grammar and punctuation, or how to format a manuscript, or write a query letter.

Then write some more.

LISA FAIN

LISA FAIN

Craving Tastes of Home Creates Niche

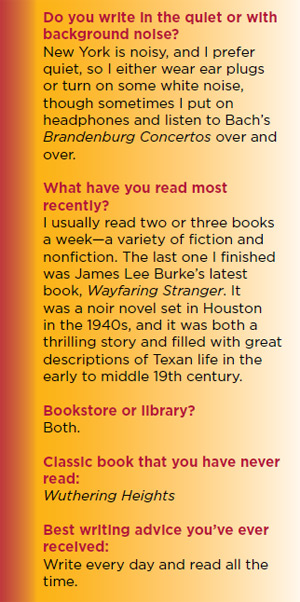

Lisa Fain ’91 is the creator of the food blog Homesick Texan. Since she was blogging before blogging was cool, she established herself early in the food blogging world. She recently completed a book tour with her latest cookbook, The Homesick Texan’s Family Table and earlier wrote The Homesick Texan Cookbook. The winner of the James Beard Foundation Award for excellence in culinary writing, education, and cuisine, she has been featured in The New York Times, Texas Monthly, Southern Living, and Saveur, and she’s a founding member of Foodways Texas.

When you attended Austin College, what were your career goals?

When you attended Austin College, what were your career goals?

LF: I always knew I wanted to do something with words. When I was in school, my aspiration was to be a movie critic at a newspaper or magazine. While that shifted a bit, I knew that writing would play some role in what I wanted to do with my life.

New York is a long way from Austin College. How did you get there?

LF: Even though I’m a seventh-generation Texan, I always wanted to live in New York City. A combination of movies, books, and television shows made me think it was the most incredible place in the world. When I was 25 and living in Austin, I was offered a job managing a bookstore in New York, and I took it, moving up there with a bunch of Texan friends. I soon shifted to magazine work and was an assistant managing editor at a magazine called Advertising Age.

Seems a long way from advertising to where you are today?

LF: While indeed I did discover that New York had all the art, architecture, music, and movies that I’d dreamed about, the thing that it didn’t have was Texas food, and this was devastating to me. Sure, there were a few places offering Tex-Mex and barbecue, but they weren’t very good, to be honest. So finding tastes of home in New York City became my obsession. And since I couldn’t find what I wanted at a restaurant, I started cooking Texas food for my friends, Texans and non-Texans.

Fast-forward 10 years and the new communication medium known as blogging had taken off—and as I loved to cook, take photos, and write, I decided to start a food blog chronicling my quests to recreate Texas food in my New York kitchen. At first, the blog was simply a way to connect with family and friends, but I discovered there’s a whole world of homesick Texans out there, as well as plenty of readers who simply appreciate good comfort food. So the blog took off, and I started writing articles for magazines and also began receiving recognition for my blog from a whole host of publications.

What was an early indicator that this was more than a friends and family update? What steps did you take to “take it big”?

LF: I soon discovered that there was not only a whole world of homesick Texans who also missed the same things that I did, but likewise the blog appealed to people who just appreciated good food and stories about connecting through food with both your heritage and those you love. While I still had my full-time magazine job in 2010, a literary agent approached me about writing a cookbook. I wrote a book proposal over a weekend, and then the book sold in one day. At that point, I decided to quit my magazine job and pursue this full time.

What’s the biggest difference between developing your cookbook for print and keeping your blog fresh and updated?

LF: Cookbooks take a lot more work, as the recipes and writing go through more vigorous process, as I not only have the cookbook recipes tested by outside testers but I also work with a developmental editor and a copy editor. Likewise, in a book, you’re limited by space constraints, so you can only say so much in a head note, for instance. On the blog, however, I can go on for as long as I want, as there are no space constraints. (Though I’m not sure if this is a good thing or not!) Also, I take all the photos in my books and on my blog, and the quality level of the photos needs to be much higher for the books than on the blog.

As a successful writer, what advice would you give students considering a career in the field?

As a successful writer, what advice would you give students considering a career in the field?

LF: Write every day, and read books instead of watching television. Likewise, know that it takes a lot of hard work, and you have to be disciplined. Even if you feel blocked, just keep writing, even if you think it’s not your best effort. It’s true, chances are your first draft will not be all that great, but that’s okay because you can revise it and make it better. The important thing, however, is simply to write and get that draft down in the first place. Everyone has a method that works best, but I’ve followed Anne Lamott’s advice to write first thing in the morning before I talk to anyone. This way, I approach my writing with a clear head.

While being published is a wonderful thing, you should write because it brings you great joy, as that is the one thing that will sustain you when you’re receiving rejection letters. It took me 15 years of rejection until I finally got published, but I never quit writing because I had fun doing it.

ROBERT LEWIS/STIKMANZ

ROBERT LEWIS/STIKMANZ

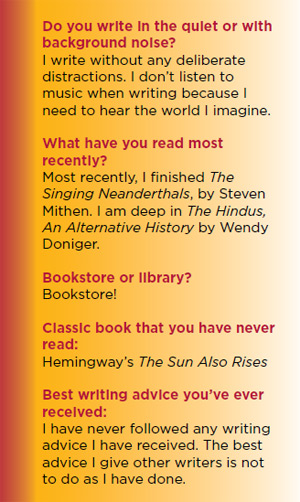

Out of this World — Writing in another reality

Robert Lewis ’78, who writes as his alter ego Robert Stikmanz, has followed his dreams. And as a “non-fiction fantasy writer” you could say he is living the dream. Stikmanz’s novels, based on a culture of his own design, get deeper and more intricate as they go. Stikmanz is multi-talented in video production, illustration, writing, and composing. His most recent book, Rose Moon, was released in October. To learn more about The Land of Nod and Stikmanz, visit his website.

Your work on the Nod series has been described as “mind-bending.” Do you recall when and how the first notion came to you?

Your work on the Nod series has been described as “mind-bending.” Do you recall when and how the first notion came to you?

RS: The entire world of The Hidden Lands of Nod evolved from a single image that appears in none of the works. In May 1984 (I documented the month), the picture popped into my mind. It was so vivid that I began to explore the story behind it. And the story that followed. And stories running alongside in parallel. My first prose sketches of alternate realities embedded in how we understand the world date to 1983, but the narrative source of The Hidden Lands of Nod rose a little later from that forceful, single image. Curiously, the image does not fit naturally into any of the fictions I have written or planned. Call it propulsive back story.

Who do you imagine is an avid Stikmanz reader? Who do you have in mind when you write?

RS: For several years, I traveled regularly to science fiction conventions. One great benefit of those appearances was that I met a couple hundred readers of my work and connected personally with dozens of them. The best generalization I can make is that they are smart, creative, and unorthodox.

I don’t give much thought to audience until I begin re-writing. I keep in mind four or five friends who have been tough, honest readers since I began sharing the fruits of my secret labors. They are the generous souls to whom I can turn with a third or fourth draft and say, “Tear it up,” and they will, lovingly. They also are the same cadre who, having read a lumpy early draft, will still be first in line for the published book.

As its creator, do you ever think in Dvarsh?

RS: In a limited way, yes. Since there is no one with whom I can speak Dvarsh, I have never become fluent, and it flows most readily to mind when I am actively engaged in its development. I cannot say I think readily in the language, but I have assimilated enough chunks to know the general shape or sound of an expression before I pull out my grammar notes and lexicon.

Describe a “day in the life” while you’re actively working on a project.

RS: Every day, I attend to some facet of The Hidden Lands of Nod. This past weekend, I made the final edits on my new novella, Rose Moon. To break up time staring at a computer screen, I alternated editing sessions with sessions at my drawing table, working on the “cover” illustration for the novella’s coming release as an e-book. Saturday, over lunch, I worked on the character set for a Dvarsh font, on which development of a long-awaited Dvarsh-English dictionary depends. Over dinner, however, I worked on a new draft of my third novel, Sleeper Awakes, which has been out of print since I left my original publisher. Sunday evening, after finishing the Rose Moon edits, I worked on new graphic elements for a redesign of my web presence, until the last active hour, when I returned to the Rose Moon drawing. The work week requires more discipline, as after a day at my job, I may have only a couple hours of effective focus. Those evenings are usually allocated to whatever has the nearest due date, fills the biggest promise, or opens the most subsequent possibilities. Or to whatever surprise capriciously demands passionate attention.

My creative life is overwhelmingly devoted to The Hidden Lands of Nod as a single, encompassing initiative. I have outlines, notes, and partial drafts of the fiction still to write. Design is near complete for a new edition of Nod’s Way, a fantasy divination system that includes the ancient wisdom book of the Dvarsh. The font and dictionary mentioned above are in development. Their importance is not least to me as I complete a body of texts in Dvarsh. And then there are the illustrations. I produce at least one finished image for each text or artifact. Those single images, however, are rooted in sketchbooks that are part of my imagining process, never meant to see public light.

In some ways, a more pertinent question might be, “Do you have a life apart from your job and The Hidden Lands of Nod?” As a socially awkward introvert, my only response can be, “Um, maybe.”

What other jobs have you held while pursuing your art?

RS: For the past 14 years, I have worked for Cycorp, the artificial intelligence software company, where I am deputy director of operations. Before that, I spent a little over three years as administrative associate to Jody Conradt, the legendary University of Texas women’s basketball coach. From 1983 to 1997, I worked in the graphics industry, both as a manager and as an artist/designer. Since about 1992, I have maintained a sideline as a video artist.

RS: For the past 14 years, I have worked for Cycorp, the artificial intelligence software company, where I am deputy director of operations. Before that, I spent a little over three years as administrative associate to Jody Conradt, the legendary University of Texas women’s basketball coach. From 1983 to 1997, I worked in the graphics industry, both as a manager and as an artist/designer. Since about 1992, I have maintained a sideline as a video artist.

As a graduate of Austin College, how did the liberal arts education prepare you for a life as a writer?

RS: As for how a liberal arts education prepared me for this creative life, to my previous answers I add one word: Sprezzatura!

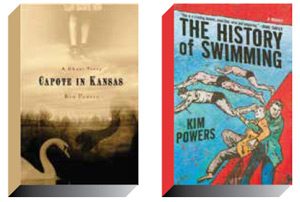

KIM POWERS

KIM POWERS

Upstaged by Opportunity

A theatre major’s journey to the newsroom

Kim Powers ’79 may have expected to walk through a stage door somewhere in New York City; opportunity came knocking in an unlikely way at an unlikely place. Years later, Kim has received an Emmy and a Peabody award for his writing in 9/11 coverage for Good Morning America. His acclaimed memoir, The History of Swimming, was a noted Barnes & Noble’s “Discover Great New Writers” selection. He works now as senior writer for ABC’s weekly news show, 20/20. Although a long way from the stage, it’s been a dramatic journey. Kim received an Austin College Distinguished Alumni Award at Homecoming 2014.

You left Texas to pursue theatre in New York City?

You left Texas to pursue theatre in New York City?

KP: Yes. I got there a little accidentally. I had done summer theatre work at Williamstown Theatre Festival in Massachusetts before and after my senior year at Austin College. Of course, I met many people from that area and they were all saying, “Hey, come to New York.” I had applied to graduate school, but did not get accepted and was devastated at the time. Since going to New York sounded like more fun than coming back to McKinney to figure out what to do, I went. That was 35 years go.

Many journalism majors would love to know how you landed the job on 20/20.

KP: Well, it had nothing to do with planning. I had spent 20 years not working as an actor but in executive development. I would search out film and television projects to produce, through the publishing industry. It was full of smart guys like me looking for work to produce. After a while, I began writing on my own and promoting myself.

At the same time, I was volunteering at a place called God’s Love We Deliver, around 1996. We were serving meals and helping in the AIDS community. Every Sunday, I would go there with a group of people, and one guy always left for work at 3 p.m. I thought, what kind of job starts at 3 on a Sunday afternoon? So, I asked, and turns out he was a writer for Good Morning America. That’s when the shift starts, and they write into the night.

I was out of money and out of work, so I mentioned I’d like to do something like that. He said, come on out; they needed temp workers, and I showed up and auditioned for the job.

I was surrounded by journalism majors from Columbia and such, but I could tell jokes. I knew a lot about pop culture and really approached it from a human-interest point of view. I didn’t even know which rules I was breaking … who, what, when, where, and all that. I tried to be heartwarming.

How did a liberal arts education prepare you to succeed there?

KP: I think the liberal arts education gave me a broader perspective. I had taken a range of classes including history, psychology, and some English. I wanted to write as if for myself. Smart and not formulaic.

Do you think it’s still possible to work “up” in journalism like you have done?

KP: It is very competitive now. We have interns at ABC, and many of them come from journalism programs. They’re the editors of their papers, run the school radio station, and such.

What are the unique demands on a news writer today?

KP: It’s so hard. Any story has a life cycle of maybe 36 hours. Not even two full days. Let’s say you’re talking about something special such as the deaths of Robin Williams or Joan Rivers. If it breaks on a Tuesday, then by Friday night on 20/20, there’s not much we can add. By remaining topical we see more in the ratings. We hang it on that peg. The language always has to be “what’s new” or “for the first time” or “Exclusive to 20/20.” It’s difficult.

It’s been a number of years since you published The History of Swimming and Capote in Kansas: A Ghost Story in 2008 and 2009. Do you have plans for another book?

KP: Yes! Actually I have just finished a new book; it’s a commercial thriller, Dig Two Graves. It’s a very big concept, and we’re looking into film rights. I hope to have an announcement soon about that.

Do you have someone in mind to cast in the movie?

KP: Can I tell you? When I first thought of it, as a screenplay, I thought of Harrison Ford as a young, strapping actor. That tells you how long it’s been. Now I’m thinking more Ben Affleck.

KP: Can I tell you? When I first thought of it, as a screenplay, I thought of Harrison Ford as a young, strapping actor. That tells you how long it’s been. Now I’m thinking more Ben Affleck.

What advice would you give a student who is interested in a writing career?

KP: I would say you have to write every day. To develop the muscle you can’t wait on a muse. The muse will never come. Ten thousand hours of writing will make you a damn good writer. As scary as it is.

I also would say, do your homework. There are millions of resources to find out about publishing and getting an agent. Don’t just ask someone. Dig.

And then, work through your writing as much as you can. You never get a second first chance. No one will listen to “well, that was just a draft.” There won’t be another chance.

JENNIFER WENZEL

JENNIFER WENZEL

Seeking a Scholar’s Life

Jennifer Wenzel ’90 completed majors in history and English at Austin College, and her career is an excellent response for the common question of what graduates do with an English career. A member of the faculty at Columbia University, Jennifer travels, teaches, and brings ideas to the top so others may also learn. She is an associate professor in the Department of English and Comparative Literature and also the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies. In 2009, she published her first book, Bulletproof: Afterlives of Anticolonial Prophecy in South Africa and Beyond. She has many published papers, two current book projects, and a co-editing venture within the field of literature, history, and the environment. To learn more about Jennifer, visit her website.

What were your goals when heading to graduate school after Austin College?

What were your goals when heading to graduate school after Austin College?

JW: I loved literature and loved college and wasn’t ready to be finished with either. I couldn’t have said it this way then, but I wanted an academic life.

Did you always want to teach on the college level?

JW: I went to Austin College for the Austin Teacher Program, first thinking I wanted to teach in elementary school, then high school. But I had some gentle prodding all along from my mentor Jim Ware in philosophy and English faculty like Bill Moore and Carol Daeley that perhaps I was best suited for graduate school and college-level teaching. It took a long time for me to recognize myself as the scholar that they seemed to see early on. But I am still completely fascinated, at an intellectual level, with how young children think.

What percentage of your time do you commit to writing for publication?

JW: It’s hard to quantify in that way. During the academic year, I’m mostly deadline driven and have to steal little bits of time from teaching, going to lectures, committee work. In the summers, I tend to get more time to work at my own pace.

Do you have set hours when you write?

JW: If only. On days that I don’t have to go to or prepare for classes or meetings, I like to settle in by around 9 a.m., plan to write for an hour or two, and, if I’m lucky, be eager and able come back to it after lunch.

How would you describe your readers?

JW: Most of my work to date has addressed an academic audience of scholars and students interested in postcolonial literature and history (particularly Africa and South Asia), memory studies, and the environment. In the past few years, though, I’ve been involved in building the environmental humanities, which has an explicit commitment to engaging broader audiences and bringing a humanities perspective to public debate on environmental challenges, like climate change or fracking. Some of my favorite pieces, like “How to Read for Oil,” were written for the newsletter of the English Department at the University of Michigan, which is read mostly by alumni. I have a short piece online about climate change that is cited in the Wikipedia entry for Anthropocene; that’s pretty cool!

So much of the professional writing I do will never see the light of day: confidential letters of recommendation, reviews of book and article manuscripts, and tenure reviews all have miniscule audiences, but the stakes are so high, demanding such meticulous reading and canny argumentation, that I sometimes feel (and fear) they’re my best work.

What role has travel played in determining what you write?

JW: I spent a summer in India in 1992, basically on a lark after I left the graduate program at Indiana. I had an epiphany there—during a sleepless night on a rooftop terrace, complete with a full moon and a lone cow wandering the street below (it’s so cliché, but totally true!)—that my longtime love for literature might be combined with my budding interest in India and the postcolonial world more broadly. Since then I have been lucky enough to travel widely, mostly for work, but even on vacations to places like Guatemala, Martinique, or Portugal, I’m seeing the sights through the lens of colonialism and the slave trade. And I try to keep my eyes open for suggestive images and stories to use in my work, whether it’s a local TV news report about abandoned houses full of used tires in Detroit, or a photograph in the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg that became the starting point for the introduction to Fueling Culture: Energy, History, Politics, a book I’m co-editing.

How does reading make you a better writer?

JW: In more ways than I can know or say. It’s all about fluency, really, like playing a musical instrument: the daily practice that lets you hit the notes in tune, play the score with precision and style, and learn to improvise and noodle around. Taking inspiration from masters is important; I read Anthony Lane and Hilton Als in The New Yorker because they so often elevate cultural criticism to an art, in a way that leaves me in admiration, and occasionally, awe. But I’ve also learned so much from reading and editing others’ unpublished writing in a supervisory capacity; articulating the principles of good writing to apprentice writers and tinkering with their prose has made me more conscious of my own failings and prodded me to work harder to say what I mean in a way that is intelligible.

How did the liberal arts education from Austin College help prepare you for your career?

How did the liberal arts education from Austin College help prepare you for your career?

JW: In a more specific way than you mean, perhaps, in the sense that I quite literally would not be where I am now without Austin College faculty who so generously took an interest in me early on and pushed me toward a scholarly career. More broadly, though, before there was Google or Wikipedia I had Heritage of Western Culture and a wide range of courses that introduced me to various disciplines, and, more importantly, a sense of the rewards of curiosity and the joys of being able to think, read, and converse across disciplines, historical periods, and geographic regions. And, the delight of discovery: I found secret passions for evolutionary biology and Chinese literature that never really went anywhere but were nonetheless precious as new things to know and ways to think. At Austin College, I learned how to learn and how to love learning deeply.

How can college students get the most out of their education?

JW: Seek out great teachers. There’s nothing like being in the presence of a mind on fire.