By Vickie S. Kirby

Photos By Jim Haberman (Copyright)

ays start at 4 a.m. with a 1-mile walk to the jobsite. The work itself is hot and dirty, sometimes in cramped and confining spaces that leave workers bruised and bleeding by day’s end. Dr. Martin Wells, Austin College Assistant Professor of Classics, loves every minute. For more than 20 years, he has spent his summers on archeological excavations—and now, he shares that experience with his students.

ays start at 4 a.m. with a 1-mile walk to the jobsite. The work itself is hot and dirty, sometimes in cramped and confining spaces that leave workers bruised and bleeding by day’s end. Dr. Martin Wells, Austin College Assistant Professor of Classics, loves every minute. For more than 20 years, he has spent his summers on archeological excavations—and now, he shares that experience with his students.

Duos of students accompanied him to Greece’s ancient city of Sikyon in summers 2014-2016, and for the past two summers, students have joined him in Huqoq, Israel. John Huggins ’19 traveled with Wells in 2017. Just to be part of the field school takes commitment as the $6,500 expense is steep for a college student. Huggins’ parents helped, and he worked lots of extra hours to afford the trip; he has no regrets. In fact, he returned in 2018 and has plans to make the trip in 2019.

Research at the ancient site in Israel began in 2011 under the direction of the Huqoq Excavation Project, led by archaeologist and site director Jodi Magness, and a consortium of colleges and universities that now includes Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (where Magness is a professor), and the University of Toronto. Assistant director is Shua Kisilevitz of the Israel Antiquities Authority and Tel Aviv University. In late 2018, when the first round of publicity about the dig’s recent findings were released, Wells was excited that consortium membership put Austin College’s name before audiences around the world.

Huqoq is an ancient Jewish village near the Sea of Galilee. Wells said that in the 5th century CE, a rectangular, basilica-style synagogue with huge columns surrounding a nave sat in the center of the village. He believes it was abandoned after some time, perhaps a few hundred years, and later destroyed, possibly by an earthquake. When destroyed, those columns crashed onto the mosaic

floor beneath.

How is that history known? Members of the excavation have been at work since 2011, digging up history and reading the story that the stones and artifacts tell. Wells is the architecture specialist for this dig. It is his responsibility to study and reconstruct the synagogue from the unearthed site, as well as the later structure built there.

In the 12th or 13th century, builders used the synagogue columns and remnants to create a foundation, cementing it all together, and constructed another building on the spot. Once the excavators dug below this foundation level, Wells could see the building blocks of the original synagogue. Getting to them was a challenge.

He and Huggins worked together to take apart a portion of foundation of that later building. “I remember thinking that this destruction was very much a summing-up of archaeology: breaking apart the cement, taking this piece of the wall apart to see how it was made, needing to get it out of the way to get to other things,” Wells said. “In taking that apart, we found fragments of the beautifully carved columns. Discovery can be wrapped up in breaking cement, cutting knuckles, heavy lifting, and the really careful work so that you don’t destroy evidence. That was one of those moments of recognizing ‘this is what we do,’ and everything else fades away. I have those maybe 10 times a season.”

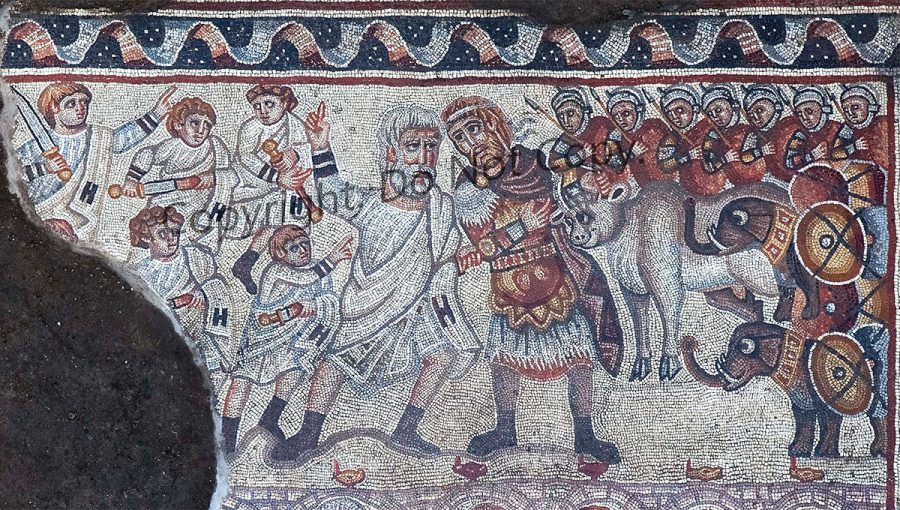

Every discovery is important and provides historical information. The mosaic floors have been significant finds for the team as some of the panels have no parallel elsewhere, according to Wells. Some depictions are clearly biblical—Noah’s ark, Jonah, the parting of the Red Sea. Other mosaics portray what could be a meeting between Alexander the Great and a Jewish high priest, the signs of the zodiac, and the Greco- Roman sun-god Helios. Other panels perhaps show scenes of the village—harvesting dates, people going about their daily lives.

While the unique panels are amazing, the finding of the ordinary is part of the magic to Wells. “I am so pleased to share this with students who can put their hands on the ancient world, have their own sense of discovery, and find something that speaks to how people lived,” he said. “I love watching students make connections and see that people did the same thing we do, but just with different stuff—they ate, got together, worshipped, and had a business.”

While the unique panels are amazing, the finding of the ordinary is part of the magic to Wells. “I am so pleased to share this with students who can put their hands on the ancient world, have their own sense of discovery, and find something that speaks to how people lived,” he said. “I love watching students make connections and see that people did the same thing we do, but just with different stuff—they ate, got together, worshipped, and had a business.”

As is always the case with experiential learning, ideas are no longer abstract, as they might seem in the classroom setting. “Being there makes the ancient world not so strange; they see a common humanity, a common human experience,” Wells said. “It’s really fun and exciting to put together the story of how people lived. I enjoy bringing knowledge of the ancient world to the academic world and to the public.”

Huggins knew a bit about the ancient world when he arrived at Austin College, but he didn’t know what he wanted to do with it. He’d taken five years of Latin and enjoyed it. He considered teaching Latin or English as a career—until his first education class at Austin College when he realized, “I was not equipped for teaching.” In a classics course, he met Wells and heard about the opportunity to go on an excavation, and so his future changed.

Of course, Huggins had grown up watching Indiana Jones and had some stereotypical ideas in his head. The dig was nothing like that … no booby traps, no mummies. Sometimes there was treasure, but Huggins quickly was caught up in what was real about the experience. “The dig wasn’t, for the most part, about the finds,” he said. “We were not digging to find a ‘thing.’ We were finding things that help put together a picture about the place and its people.”

Immediately Huggins liked being in the field, researching and piecing together what was in the ground. He enjoyed the hard, sweaty work and the need to engage both mind and body in the effort. “When you’re brushing the dirt away from a delicate piece, you may not hear a word spoken for hours,” he said, “but your mind is totally on what you’re doing.”

The expanded cultural opportunities did not escape Huggins, who saw some preconceived notions about the Middle East fall away, in addition to connecting the past to the present. “The world is so small but so big,” he said. “We could be at this centuries-old site one day and the next in Tel Aviv, with its skyscrapers and every modern amenity. I think about Jericho being one of the oldest cities in the world—and today, it is totally modern.”

In the old, Huggins is finding the brand new. He is currently applying to master’s and doctoral degree programs in classical archaeology; it’s likely his discoveries are just beginning.

In the old, Huggins is finding the brand new. He is currently applying to master’s and doctoral degree programs in classical archaeology; it’s likely his discoveries are just beginning.

Read more about this Excavation Story.