All of Don Salisbury’s 34 years of research boil down to two simple questions: Who are we? What is our place in the universe?

All of Don Salisbury’s 34 years of research boil down to two simple questions: Who are we? What is our place in the universe?

With every project, the professor of physics gets a little closer to an answer—theoretically.

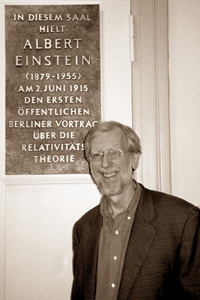

Salisbury, professor of physics and a member of the Austin College faculty since 1987, specializes in the kind of theoretical physics that deals with the nature of time and space. He tries to construct theories to explain phenomena such as black holes, dark matter, and time travel.

The best-known leaders in his field are researchers like Stephen Hawking and Albert Einstein. In fact, Salisbury’s thesis advisor as a graduate student was Einstein’s assistant. Salisbury’s fundamental training in physics began with Einstein’s general theory of relativity and has kept up ever since.

Einstein is part of Salisbury’s inspiration to keep plugging at near-impossible problems. “Sure, he was a genius, but that characterization alone really doesn’t illustrate the full picture. He never gave up,” Salisbury said. “The essential ingredient is not so much inherent intelligence, because everyone has that, but it is persistence. I think that characterizes most scientists.”

Einstein is part of Salisbury’s inspiration to keep plugging at near-impossible problems. “Sure, he was a genius, but that characterization alone really doesn’t illustrate the full picture. He never gave up,” Salisbury said. “The essential ingredient is not so much inherent intelligence, because everyone has that, but it is persistence. I think that characterizes most scientists.”

Salisbury is trying to resolve what he calls the “fundamental unsolved problem in physics: attempting to merge Einstein’s theory of relativity with quantum mechanics.” Quantum mechanics deals with subjects such as the structure and motion in an atom, while Einstein’s theory is about massive objects like stars, galaxies, and even the whole universe. “Those two theories are inconsistent with each other, and no one has yet succeeded in synthesizing an equation that combines both,” Salisbury said.

The problem is this: Einstein’s theory says space and time don’t exist as separate, fixed entities; time and space don’t exist outside of the universe. But quantum mechanics depends upon the idea that time is an independent external parameter. General relativity says that time is meaningless without a measuring device. But quantum mechanics then says that time must be inherently uncertain. Without being sure that time is the same everywhere, the theories completely fall apart. The challenge is combining a theory with a flexible perspective of time with a theory with a constant perspective.

The problem is this: Einstein’s theory says space and time don’t exist as separate, fixed entities; time and space don’t exist outside of the universe. But quantum mechanics depends upon the idea that time is an independent external parameter. General relativity says that time is meaningless without a measuring device. But quantum mechanics then says that time must be inherently uncertain. Without being sure that time is the same everywhere, the theories completely fall apart. The challenge is combining a theory with a flexible perspective of time with a theory with a constant perspective.

The theory of relativity already impacts us: without it, global positioning systems wouldn’t work. They are based on Einstein’s theories of space and time.

Salisbury’s research deals with a tricky question: What would our perception of time be if we had an equation that solved the quantum mechanics versus relativity problem? “That’s right; I’m trying to answer what it would be like if we had a theory that doesn’t currently exist,” Salisbury said.

It’s a challenge. “There’s a sense in quantum mechanics that general obviously inconsistent observations of phenomena all can be true at the same time,” he said.

As well as traveling the world to give lectures on his research—he speaks English, Spanish, German, French, and Italian, Don recently was in Pereira, Colombia, where he taught a short course on Einstein’s path to relativity theory. “I’ve always been interested in history and the larger social context,” he said. “I am convinced that the more aware one is of the path that has been taken to get to our current view of the universe, the better one can understand and be better prepared to make improvements. There is no end to the kind of improvements we could make.”

For this project, he has visited many contemporary leaders in the field and read extensively about past leaders. 1911 is a centennial anniversary of Einstein’s theory of relativity, and Salisbury and his colleagues have integrated that milestone into their research. “We asked ourselves how history could have been altered, if, instead of the direction he took, he had taken the heuristic approach that led to quantum mechanics in the 1920s. It leads to some surprising conclusions,” he said.

Salisbury has an unusual dedication to his research, which he thinks is beneficial to his students. “I hope I can pass that idea to students, that if there are mysteries they want to solve, they are capable. I hope to be that role model,” he said.

“Keep thinking. There’s no end to the mysteries out there,” he said. “Celebrate the unknown. It’s something we have to come to terms with as members of the human race. It’s essential to progress.”

Comments? Email editor@austincollege.edu.